Chris Alice Kratzer’s new guide to The Social Wasps of North America stands to revolutionize the future of field guides. It certainly sets a new standard in many ways, through methodology, organization, and sheer honesty. It is my pleasure to recommend this wonderful reference without reservation.

This is a self-published book from Owlfly Publishing, one arm of Kratzer’s company, Owlfly, LLC. The other branch is an engineering firm. Kratzer has not only avoided all the usual pitfalls of self-publishing, she has taken great pains to make every aspect of that enterprise respectful and sustainable, right down to her choice in the packaging vendor she uses.

Why is this book so unique and important? Perhaps the most obvious feature is the geographic coverage. Kratzer rightly defines North America as everything north of South America. Most natural history publishers, and authors, would consider that to be overly ambitious, confusing, and impossible to execute given the increased biodiversity south of the Mexican border. It helps to choose a taxon that has relatively limited diversity, and social wasps in the family Vespidae do fit the bill nicely. However, one should not overlook the statement this book makes about inclusiveness. This book is useful to indigenous peoples in those other nations, as well as people traveling from other places. A Spanish translation, in digital format, will be available by the end of 2021, but if a publishing house is interested in producing a hard copy, please contact Kratzer at Owlfly Publishing.

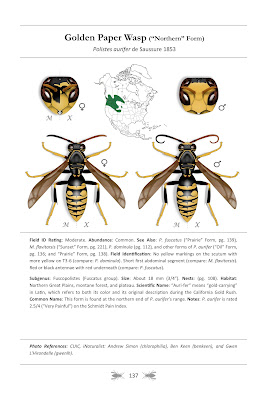

This book also marks a return to illustrations, rather than photographs, as the best means to visually communicate each species. Kratzer is a master of digital renderings. Social wasps are maddeningly variable in color pattern, so she ingeniously fused the most common xanthic (mostly yellow) and melanic (mostly black/dark) forms of each species into a single drawing, capitalizing on the bilateral symmetry of her subjects to do so. Brilliant. Kratzer essentially crowdsourced her references by utilizing pinned specimens from many curated collections, and images of living specimens from the iNaturalist web portal. She gives credit to every single individual who furnished the material. Unheard of. Each species account includes female and male examples, plus queens, where relevant. Range maps are included. Photos of living specimens, and their nests, are featured under descriptions of the genera.

The first seventy or so pages of the book serve as an introduction and overview of social wasps, their biology, role within ecosystems, and how they impact humanity. This alone is worth the price of the book. The writing is outstanding in accuracy and honesty:

“All of the information in this book is wrong. All of it. Wasps are an appallingly understudied group of organisms, to the point that even this book – the most complete visual guide of social wasp to date – is built precariously upon the edge of a vast, unsolved jigsaw puzzle.”The grammar is impeccable, and the tone is exceptionally friendly and empathetic, even to those readers who want nothing to do with wasps. It is easy for someone with an affinity for maligned animals to be unintentionally hostile towards those who do not share the same perspective and opinions. Kratzer is going to make many more “friends of wasps” with this book. Did I mention that there is also a glossary and extensive bibliography with links to online versions of actual scientific papers?

Overall, Kratzer’s embrace and navigation of the scientific ecosystem, inclusive of both academic professionals and well-informed non-professionals, is admirable and even ground-breaking. Rarely does one find a reference or author/illustrator so worthy of emulating. Maybe David Sibley and Kenn Kaufman, but add Chris Alice Kratzer to the list.

Are wasps not your thing at all? Stay tuned for Kratzer’s next effort, a guide to North American cicadas, in the works as I write this. Meanwhile, order The Social Wasps of North America for a friend, directly from Owlfly Publishing.