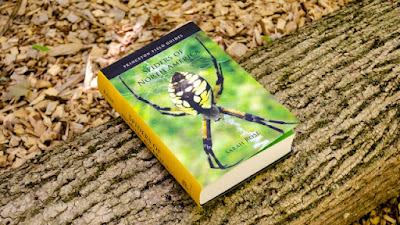

It is “Spider Sunday” on this blog, so what better to post than a rave review of the newest spider identification resource, the Princeton Field Guide to Spiders of North America, by Sarah Rose. Yes, I wrote the foreword for this book, but I guarantee that this is an unbiased review. There is far more to recommend this book than my mere two cents at its beginning.

Spiders have faced an uphill battle in the widespread appreciation of these arachnids, in part due to few easily available, and easily affordable, resources for non-scientists. The most reasonably priced books are either outdated, full of errors such as mislabeled images, or both. Until now, the only current guides to spiders have been regional in nature (California and the Pacific coast, for example), or so expensive, and/or scientifically technical, as to discourage their purchase.

Finally, we have a true field guide, organized in a manner that respects the scientific terminology, and understands the limits of macrophotography, and facilitates the identification of many spiders by non-scholars.One example of Rose’s innovative approaches is her color-coding of spider eyes. The eye arrangement of a given specimen is often key to its identification, but if you do not understand the jargon of “posterior median eyes,” or “anterior lateral eyes,” you are left spinning your wheels, if not throwing the book in the garbage. By associating the different pairs of eyes with different colors, it allows the user to make quick assessments of the creature they have in hand. The only drawback would come if you happen to be colorblind, and that is a consideration few, if any, publishers take into account.

Another way that the author organizes her book is by “guilds,” a term that in this case means the hunting lifestyle of the spider. Some spiders build two-dimensional sheet webs or orb webs, while others are “space web weavers” in three dimensions. Still others are ambush hunters or “ground active hunters.” This works well except maybe for mature male web-weaving spiders that leave their snares to look for mates, but the combinations of characteristics highlighted for each family of spiders overcomes those hurdles.

Each species entry in the book includes a range map, and verified state records. Our collective knowledge of spider distribution is relatively weak, and spiders excel at hitching rides on commerce and vehicles and other belongings, ending up far from their “normal” ranges, but here you have a good reference point for assessing the identity of most spiders you will encounter.

The images in the book are of living individuals, so all the colors and shapes are undistorted. Usually there is more than one image, to illustrate the dorsal (top) and ventral (underside) of the spider, and the color variations that the species might exhibit. Additionally, webs, egg sacs, and young spiders may be depicted, the better to demonstrate the full range of a species’ appearance and lifestyle.

The first part of this field guide provides an excellent overview of spider anatomy and biology, gives a brief and effective lesson in how spiders, and all organisms, are classified, and shares tips for observing spiders safely, ensuring that both you and the arachnid will be unharmed. Need to know the benefits of having spiders around? They’re in there. How do spiders fit into the larger picture of ecosystems? That information is also included. Did I mention there is an illustrated glossary in the back? Additional references are listed in the bibliography.

Before I end, I must offer an apology to all of you. This reference should have been available much sooner. I was the original author contracted to write this guide. It soon became apparent to me that I was not qualified to execute the project. Unfortunately, I procrastinated in disclosing that to the publisher. The least I could do was recommend a replacement, and I could not be more delighted that Sarah Rose agreed. This is a far better book than anything I could have written. If you have even a smidgen of curiosity about spiders, this reference will ignite it into a flame of passion. All the common species are in there, plus ones that you will see and say “Oh, I have got to find one of these!” Happy spider seeking, friends.